Property – The Future of Investment?

Property – The Future of Investment?

By Stuart Thomson, Managing Director, Johnsons Chartered Accountants

Traditionally a cornerstone of the investment portfolio, property has been a reliable performer for many in recent decades. However is this trend set to continue, and what are the key indicators of change in the property investment sector?

Assets’ prices rise in value when demand rises, and supply cannot meet the increased demand. Property prices have risen consistently since the 1990s due to:

- general economic inflation.

- the failure to build new homes to meet demand due to changes in social norms.

- a growing population and immigration.

- record low interest rates, passed onto consumers via low rate mortgages.

In trying to predict the future of property prices one needs to assess whether these four features of historic prices growth will continue. Inflation is likely to continue, but the question is whether property price inflation exceeds consumer price inflation. If they are the same, then purchasing power has not changed. Interest rates are unlikely to see lows of 0.1% again and are currently rising, but will they reach near double digits? I don’t think so. Rates need to reward saving, or we become a myopic consumer society. The speed of economic advancement has helped to maintain low rates and I believe relatively low rates will persist in the long term, but not at the rate of historic pandemic lows. There is no reason to believe that the population of Britain will not continue to grow, and immigration seems inevitable, so it appears likely that this trend will continue.

The less predictable question is around social norms. Since Margaret Thatcher made home ownership an achievable aspiration for everyone, the UK population has generally believed in home ownership as an intrinsic goal. However, is this widely held aspiration now becoming an impossible dream for many?

The chart below, from ONS data, shows that since 1997 house prices have growth significantly more than the earnings that are needed to support these prices. At no point over this period have house prices been more affordable than the prior year. How is this possible?

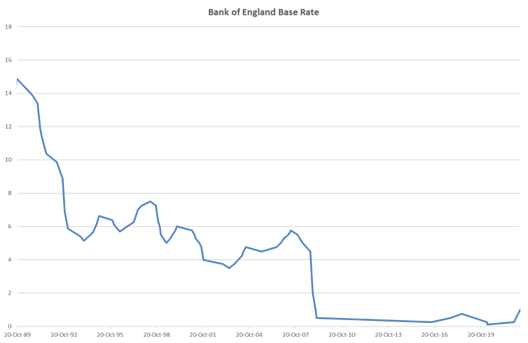

There must be some other income, or reduction in lifestyle costs, that has driven continuous property price rises. The reduction in cost has been interest rates. The chart below shows the scale of reduced Bank of England base rates tracked, of course, by Mortgage rates. Since October 1989 there has been an almost continual reduction in interest rates, driving lower mortgage costs and increasing affordability. This trend has led to an increased appetite for borrowing.

So what does this mean for the future of property prices? In my view, the property growth seen over the last 30 years is unlikely to repeat itself, as there were structural, one-off reasons for previous growth. Going forward, property is more likely to follow earnings inflation. This will be enhanced by the leverage of borrowers paying for the inflation through higher mortgage interest rates which have imbedded inflation built into the interest rate. This does not make property a bad investment, however investors should probably not expect the growth of the past to be replicated in the medium term.

This is not a surprising conclusion. Asset price growth tends to taper off at some point, once everyone anticipates the growth, and market forces find more attractive investment opportunities. Perhaps we should be investing in banks, considering the likely increase in interest rates? And yet banks are still exposed to property from their security. As always, it is impossible to predict the next big thing until it happens, by which point it is too late.

Property will remain an important asset class. Not just because property represents people’s homes, and as such has emotional value, but because property is considered a stable asset against which lenders seek to lend. This creates leveraged inflationary growth. Annual profits from property may be low, but if values grow then asset wealth is compensating and perhaps, for those with high incomes, a capital growth biased investment is a tax efficient opportunity.

| £ | Year 1 | Year 2 |

| Purchase price | 500,000 | 525,000 |

| Borrowings | 300,000 | 300,000 |

| Equity/Deposit | 200,000 | 225,000 |

The table above shows that the property value has risen by 5% but the equity value (ie the growth in the owner’s stake) has grown by 12.5%. This is possible because the lender’s loan has not increased (inflation linked property loans are rare). However the lender needs to compensate as its loan has lost purchasing power due to inflation. The lender will therefore incorporate inflation into his loan and charge a higher interest rate accordingly. Where this does not occur, the lender is indicating that they have either priced the loan wrongly, or they are more concerned about the loss in purchasing power by not lending, in effect keeping their own equity under the bed!

One major distortion in the above analysis is taxes. Recent politicians have seen property investors (not owners) as wealthy, and a source of additional tax revenue. The relatively low number of property investors means that few votes are lost from this fiscal perspective. If one borrows money to create property income, then one’s marginal tax rate will be very high, and in many cases prohibitively high. We are often asked to develop strategies and structures to mitigate against this increased tax burden. But there is rarely a panacea. Avoiding one tax usually triggers another. The trick is in finding a tax to trigger, that one is unlikely (or occasionally willing) to pay.

The need for a mortgage also confers additional restrictions which most tax advisors don’t understand. There is no point implementing a fantastic tax plan when you cannot secure your mortgage, and are either saddled with high interest rates or need to liquidate in order to repay the mortgage.